OIL AND RUST

about the 'oil and rust' project

The past 15 years I have been photographing my grandparents' farm and other abandoned farms in my home county, located in southern Virginia. Making a series of artist books during an eight week book, paper and printmaking concentration at Penland School of Crafts in the Spring of 2016 pushed me to face the weight of these photographs and how their meaning for me has changed over time, as I have become more educated about the history of the place I grew up. I ended up calling the books "Oil and Rust" which then became the name of a whole collection of work that includes writing, ink making, and photography.

I have become increasingly fascinated by the old things from that place that are rotting to the ground in a metaphorical decomposition of toxic settler land culture. Within these rusting and rotting objects lie expansive untold stories and malformed ideas that came from the Virginia settling of stolen land.

There is a complex irony in ‘Oil and Rust’: Oil is the South's dirty secrets, wrapped up in a shallow facade of southern hospitality. Rust is the change and transformation of toxic social norms that weave into that charm. I pray for rust to move ideas and objects alike back into the earth. Certain institutions that govern power are being currently transmuted but are not yet dead. Other institutions are systematically still being held in place, yet the rust is building, degrading, aging things. Together Oil & Rust are a mix of depressed nostalgia and hidden southern gothic doors to a past which most white settlers don’t want to look.

What I write and feel is my own interpretation what I glean intuitively from the objects themselves. Many stories I will never know and expand out in their own mystery, but in witnessing the degradation of these settler ‘objects’, one can feel the hidden mysteries. I hope continue to paint pictures of this place with different lenses over time, witnessing its transformation.

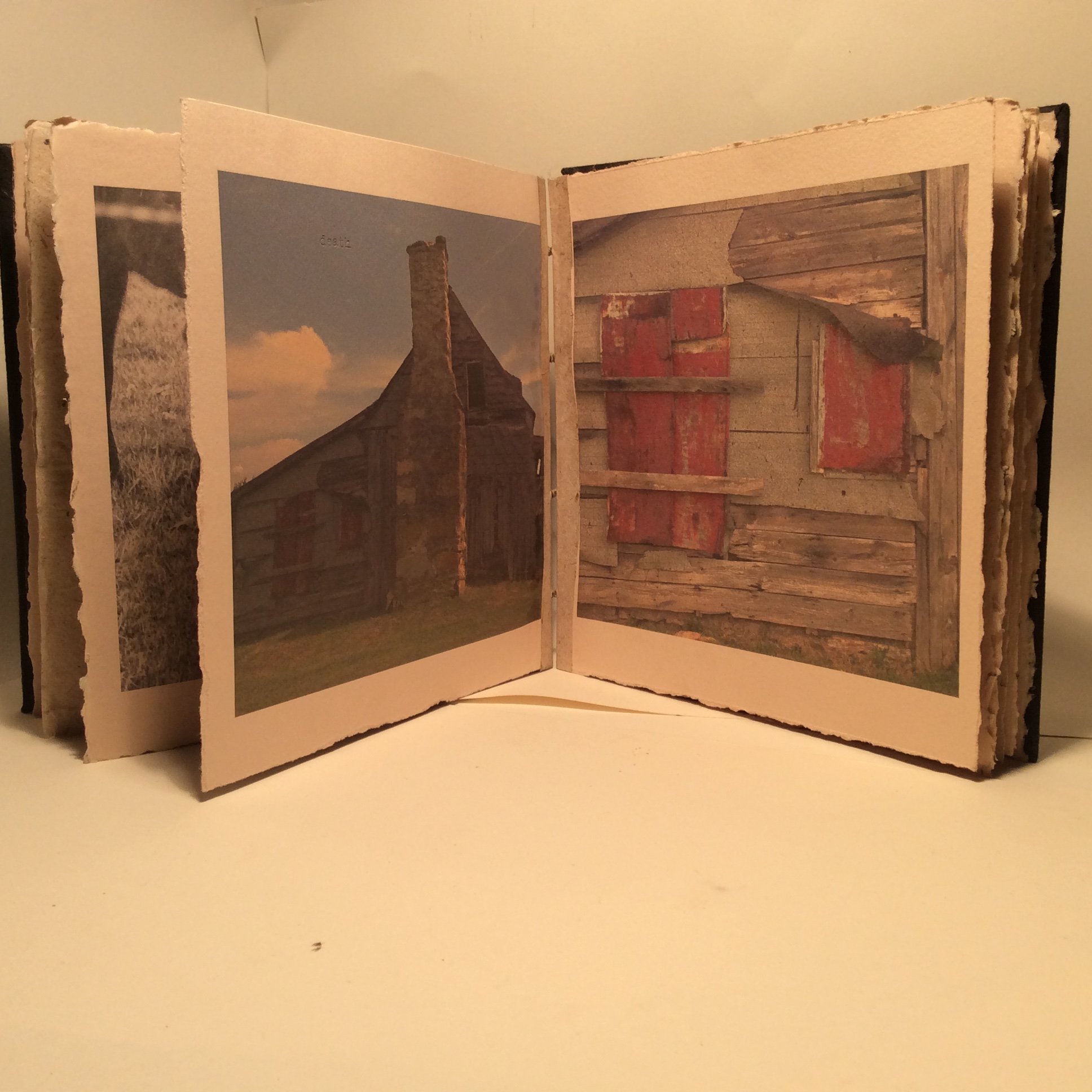

"Oil and Rust" #1, Artist Book

Printed at Penland School of Crafts, Spring 2016.

Handmade paper from kudzu root, wisteria vine, old blue jeans and flax.

Hand cut linoleum prints. Some ink is made from black walnut hulls.

Letterpress and typewriter printed text. Printed on a Vandercook and Ink Jet printer.

Photographs all mine from a period of 12 years.

Hand bound book in coptic binding.

Edition of 4.

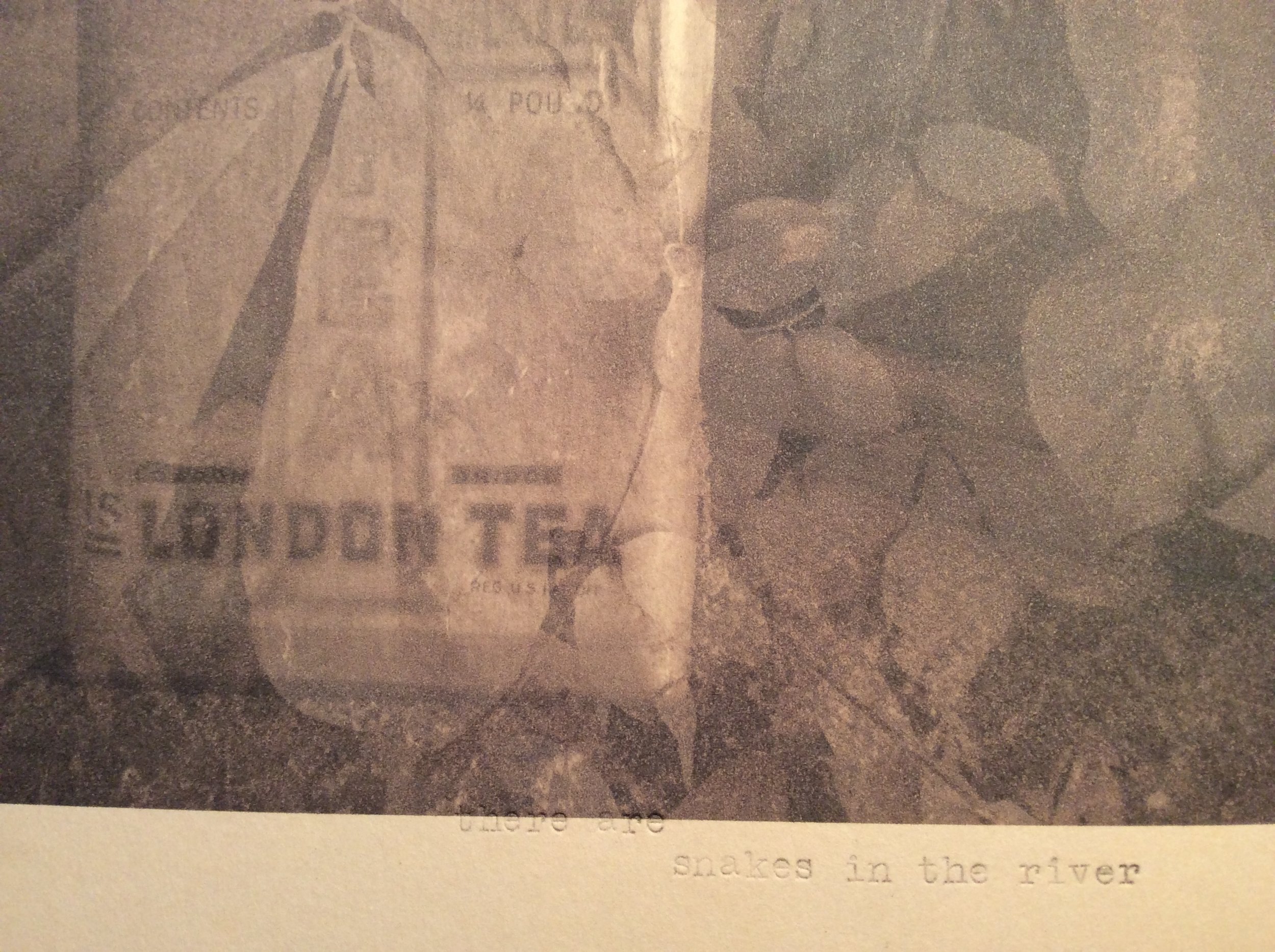

This book dives into the relationship between the lost knowledge of native plants and the history of slavery as it coincides with an intensely dependent relationship humans have with destructive agriculture. It features photographs of the region where I grew up in south-central Virginia, traditional Occaneechi land.

Through wordplay I explore the relationship to seeing the land as a place to manipulate, use, deplete and extract resources. These practices and mindset behind the brutal settling of Virginia fostered the loss of traditional knowledge of the wild plants that grow. I include native medicinal, edible and useful plants that I 'assume' would have been used by native peoples in the area. This is based on my own knowledge of medicinal plants and ecology. The living history of the native peoples in the Piedmont region of the South is barely recorded, and much is unknown.

Portrayed by using double exposed photographs, and often overlaid with more organic subjects, I feature objects representing the stark euro-agricultural relations to the land. Horse drawn implements, tools, old signs, spent oil and ropes. Many of these objects show sign of age and wear as time has changed their purpose into monuments to a past we must not forget.

The rust is symbolic yet is actually transmuting: it transforms the object into something else, is an emblem of the past. Even this destructive way of being on the land that my ancestors lived is now a closing door. Large scale tobacco and soybean farming is no longer economically viable and the farms are being abandoned, the soil is getting to rest. The ‘wild’ plants are reclaiming once again. The lichens are eating the barns. It means my cultural upbringing from a farming culture is changing, my cultural identity is fraught with a legacy of systematic and overt racism, human enslavement, land abuse as well as great resourcefulness and resilience. Some of those things need to die or shift, but with it goes a loss of the familial traditions: the sweet potato pies, the salt-cured ham, hanging fresh laundry on the line. The book visits the meeting point of many necessary losses, yet a celebration of the joyous parts of these worlds, too. Yet with this transformation, the farming way of life that revolved around growing food and touching earth, as well as being tied to the chance of a cash crop, is being replaced by box stores, or young people are moving away. What will happen to this red earth? The place sits in limbo, as cultural changes are needed to revision new ways to be in relation to land.

Images of artist book 'oil and rust #1':

Click on the images below for more information about the content shown and a magnified view of the pages.

writing archives from the series:

excerpt from 'story of place: oil and rust ii':

"The cyan will sweep the land clean. It will pass along the era of frolicking children in dusty linen dresses and black tenant farmers toiling away. The flash of hot will bury the monoliths, the homes and the linear rows, just as fast as they were born in my first memories, all undefined and held with cryptic code. The joy of homemade pie, sweet iced tea and being held by a grandma fade into the ocean of the past, but is not to be mourned or forgotten. The future holds new waves, new growth, and more pies to be made in the name of the bygone. "

excerpt from 'home as a purgatory of remembrance: oil and rust iii':

To observe myself now is strange, after all the years of what I went through being a weirdo from the south, a complicated place. This newfound attachment to sense of place here is the most overwhelming pull of heartstrings. I feel it in so many lands. The irony of so much travel, is the upheaval of what you thought you always knew: to the point where home seems like a calm respite or an undramatic boring field of corn compared to the epic landscapes and cultures of other places. I feel the land's story deeply, and for the characters that play on that land, I have empathy and love. But what is it about home that pulls me the most? The humid thick air and buggy ditches of elder, bidens, oxe-eye daisy? The undramatic rows of soil destroying GMO crops. What is it about those shapes on the land that pull me? I feel the land crying, and I cry. The layers of memory laid down on this soil and the ghosts of my genetic past, however joyful and shameful, are imbedded here and I feel them everywhere.

excerpt from 'my grandmother's gave me plants':

I tugged at her thin floral skirt with steam rising from the faded yellow linoleum countertop above me. The air was thick and damp already from long days and nights where the humid heat just wouldn't let up. I tugged at her skirt for a hug, for some attention from her tasks at hand. Retro plastic bowls lined the counters and tables, in all kinds of colors, filled with vegetables of all sorts, in different stages of break down. She put me into my wooden handmade high-chair, hand lacquered many times to seal it from children's spills and the wet parts of life itself. I see where the steam is coming from now that my vision is raised higher. A big metal pot. She, Janie, gum-ma, in her handmade floral dress, always sleeveless in humid summers to let the arm pits breathe freely, lifted glass mason jars in and out of the metal pot, each full of colorful organic shapes. Food. Green beans with the ends snapped off, we did it together on the cement front porch watching the flags flutter in the wind, the crows come by and land on the old cedar fence posts in a kind of coordinated cadence. Washed 3 times. Cucumbers with the skins removed and the pickles cut into thin green slices, stuffed into jars with an array of aromatic herbs and seeds. The ball jar recipe book out, greens, reds, yellow seemed to paint all surfaces. We'd take those strawberries too, eat them before we could even make jelly. Cutting the green leafy tops off, leaving the fruit alone, filling a matching color retro bowl of sweet reds. We'd throw white sugar on them and watch the bowl fill with liquid, waiting patiently to put whipped cream on them as the air full of moisture stuck to our skin and dripped so much sweat we had to wipe our brows with handkerchiefs. We'd laugh. Eat our strawberries covered in sweetness. Walk out into the beating sun, passing the planted Loblolly's in the yard, the thrice struck by lightening cherry tree to pick the sand splashed tomatoes, bringin' them in to be blanched and thrown into the magic pot, too. These were the days of my timeless feeling childhood. The days of day after day with my grandma, my parents at work, my papa out in the tobacco fields. She taught me something about food and putting up crops, even if it was just simply witnessing the act and seeing its importance in a home. She also showed me her version of mending, and cooking, and caring for family. My mom does these things now, later on, but growing up as a small child, it was my grandma who first led me to the plants.