This mercury in retrograde has certainly made me realize that it is okay to question hard thought out plans. And to realize that the space that seems so void looking ahead in a linear calender of time really is space for spontaneous opportunity and to fill those spaces with constant agenda don't do the soul much justice. Realizing, too, the privilege to have voids of time to fill that don't conform to a 9-5 work week. I had intended to be in Big Sur by now, knowing full well the bridges were washed out from a crazy rainy reason and it would be hard to get to see the plants there. I just talked to friends I met at the Buckeye Gathering that lived in Big Sur for years. It was explained to me that even they, longtime residents, had to move away for lack of jobs and access. The bridge won't be rebuilt for a year and even the secret side rode in is closed. So be it. The land deserves a break from humans. The Hummingbird Sage and Sticky Monkeyflower I hoped to visit there can wait until another year. And there's the Yosemite trek I wanted to do, which still might happen this summer, but I had hoped to catch it when the flowers bloom at high elevaton. Eric has family property in the park, crazy enough. From his land, which is a bare space of remnant rubble from a fire in the 90's that took the family cabin and reclamined it to the primal ethers- you can access trails that will take you to El Capitan in two days. I will be off the grid, hiking or in the woods a lot this summer, but I've been wanting to traverse this terrain for some time now. Ever since Eric told me about his time doing it.

This is the fourth year that I will be making some version of what I was calling 'Desert Wound Salve' in the past. The plants I lend stories to here in this post are some of the plants included in the salve I make. I tend to collect stories in my mind of the plants I love, and want to make my medicine filled with stories and layers of connection. The medicine is filled with my memories and experiences as well as the shadows of those that have used the plants in the past for food or medicine. I think of all the experiences the plants have had, the seasons they have been through. The things they have witnessed. This formula I've chosen because these plants I have connected with and been around the most in my California and Nevada travels.

My dad has been using a salve made from these plants for years on his skin when he normally doesn't use salves. He's olive skinned and works outdoors all year long and tends to develop questionable skin lesions from the harsh sun.

Cottonwood.

Cottonwoods at high elevation in the Grand Tetons, WY (aspens)

I thought my first experience of Cottonwood was on the west coast. But, now that I have been thinking on it all winter, really reflecting on my first experiences with certain plants, I now remember vividly first encountering it while camping for a few weeks in the Finger Lakes region of New York in 2011. I was on a friend of a friend's land, while a travel partner at the time was helping that friend of a friend work on his house. I had never explored the region. I had some time while I was there to look at the plants as well as visit my friend Mario who was studying with 7song at the time. In a wooded grove on the land, there was a big towering tree in an opening by a creek. It was one of those picturesque kind of forest grove openings, where the area around the tree was clear as if I could set my sleeping bag down right there on the soft ground and stare up at the giant limbs without any obtrusion from mid story trees. I thought the tree was a White Birch at first, as the upper limbs were white and gray- and Birch species did grow around the area. But, as my eyes wandered down the massive trunk, I realized the bark was ropey and twisted, turning a muted gray at the bottom. I was astounded by it's size. I asked the landowner, my friend's friend, and he told me it was a Cottonwood! That same summer was the first time I attended the Traditions in Western Herbalism Conference when it was at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, and here too I started to see the Cottonwoods or cousins thereof.

Black Cottonwood, Sierra Hot Springs, Sierraville, CA

You can see the resin dripping from the buds.

I know we have Populus species in North Carolina, where I lived for years. Populus being the genus of Cottonwood species and Quaking Aspen. And, we keyed Populus out on an herb school field trip at Thom and Renata's wild land in southern Kentucky. I read about the local southern Appalachian use of the sticky buds. I found a self published book written by an old resident of Sugar Creek rd on the way of life in his holler when he was growing up. It was called "Sugar in the Gourd" by Ben Garrison. I lived in that same Appalachian holler for four years and still migrate back there, just outside of Asheville, North Carolina. The author wrote about the task they had as kids to collect the buds early spring for selling just like their Ginseng and Black Cohosh harvests. I never sought the buds out back then. In Ohio, when I worked with the United Plant Savers, Paul Strauss had also talked about "Balm of Gilead" which he used in his Golden Salve and I think his cough syrup. At the time, I didn't quite understand which plant this really was. He also used the propolis from his beehives in his medicine, and I was confused because they smelled and felt like the same medicine.

Black Cottonwood, Sierra Hot Springs, Sierraville, CA

I encountered Cottonwood again while traveling in the Pacific Northwest where they grow in abundance. I was visiting friends and stopped to see Ted, who at the time was apprenticing at the Wilderness Awareness School near Seattle. I was at the school's campus with him for a weekend teacher training, and he told me I should take walks in the forest and harvest Cottonwood buds because they were perfect for harvesting at that time. The trees towered above Salal and Huckleberry, intermixed with thick groves of Western Red Cedar and other conifers. I had never quite experienced such thick wet woods. It was cold and damp in February, yet we were all warm covered in our woolens. That was the trick for laying under those Cottonwoods - wear wool and maybe take to the midstory canopy of the Cedars to keep dry.

Cottonwood by the lake, camping in the Grand Tetons, WY (I call all the Populus species Cottonwood)

During the winter, I found groves of squat small Black Cottonwoods. This was while wandering around on the Sierra Hot Springs property and the national forest beyond. Their crowns were broken off a million times sending up shoots from the base of their trunks. They grew along a dried out creek bed, one that seemed to stay dry for a few years during the recent drought in California. But this year, it is running strong. The grove was a journey to get to with the mud and snow mounds and even on my cross country skis it was difficult not to sink into the ground spots. The buds were small but easy to reach. I didn't realize they were Cottonwoods when first discovering the grove in the leafless time of the winter. Something told me to sit down, as it usually goes. After awhile of watching, I was thinking they maybe were Willows, as they also grow on the same wet corridor. Examining closer, I smushed and smelled some buds. I noticed the dead leaves on the ground all around were round and heart shaped. They were not long and narrow like most Willow. These were indeed Cottonwoods. And the leaf scars! So pronounced. Next to the lodge at the Sierra Hot Springs is the Fremont Cottonwood, big and towering like the one I met in New York, with giant fat buds out of reach. Traveling up the Sierra Valley and into Lemon Canyon on crazy dirt roads skirted by Manzanita, Redroot, Sagebrush, Black Cottonwood, and Juniper, you reach higher elevations and meet the uni-organism Quaking Aspens, another Populus.

Simple Cottonwood Linocut (with California Bay leaf and Tan Oak acorn caps)

I noticed them dominating the valleys hugging the waterways traveling through the heart of hot springs country in central Idaho, one of the most beautiful places I have ever spent time.

Several Populus species.

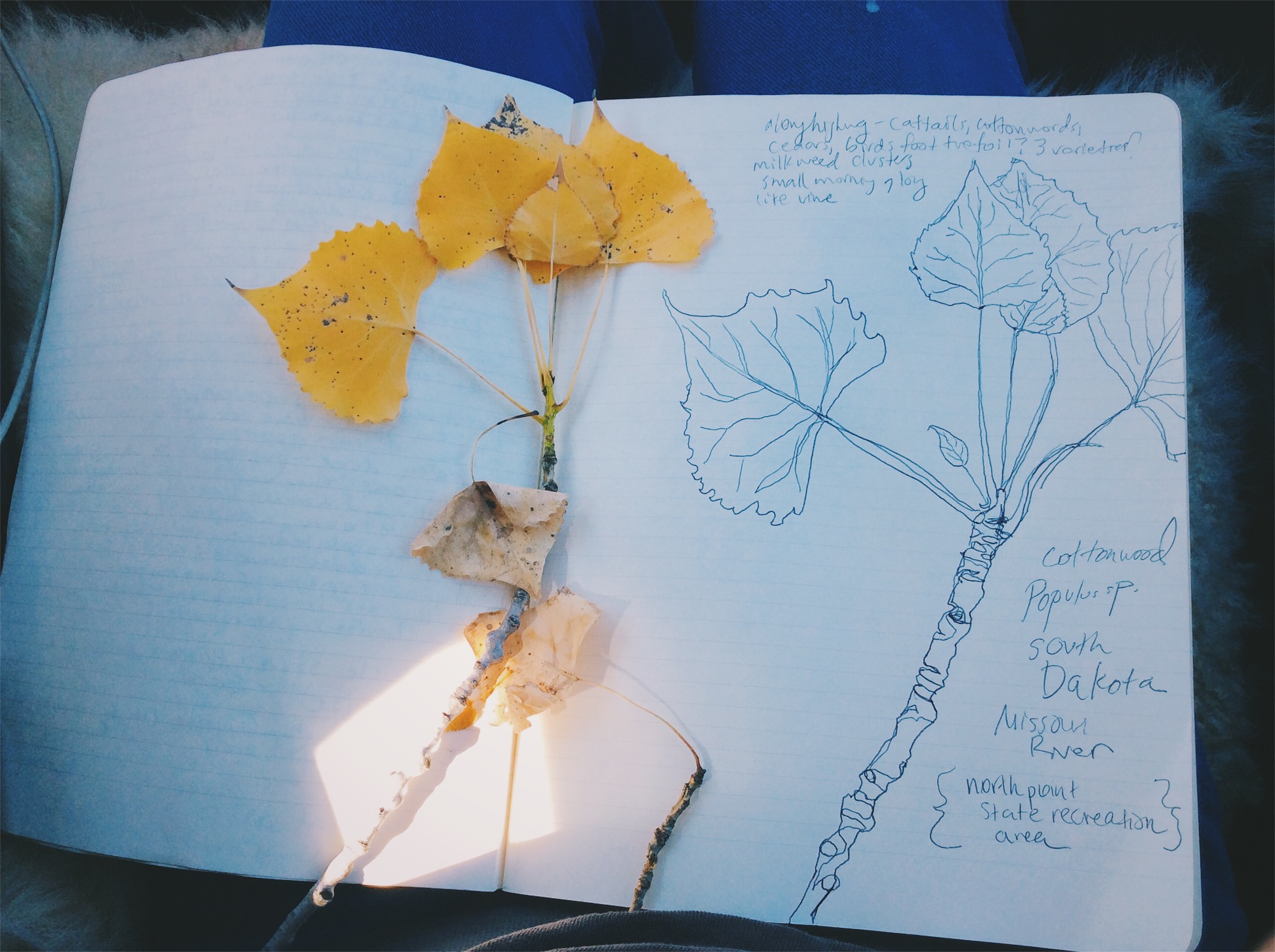

I've noticed them traveling up the Missouri River, following it from St. Louis to Standing Rock. I've noticed them in the Tetons up high and low and Yellowstone. One version grew in the Great Basin on the way up to meet the Bristlecone pines, fluttering their gold coin-like leaves in fall.

The species I use the most is the Black Cottonwood. Just because it is what I have encountered the most at the time of year they are ready to harvest (late winter and early spring before leafing out). The earthy resinous smell is one of my favorites. I don't mind the orange sticky fingers that come with harvesting them one by one, only taking a small portion from each tree.

The buds are antimicrobial and subtlely pain relieving, as well as soothing just from the smell alone.

Cottonwood / Willow / Sagebrush

COnifer pitch.

Conifer pitch. This is dried sap from any Pine family (Pinaceae) species. In most places I have ever lived, there have been different species of Pines, or trees in the Pine family. Not to be confused with trees in the Cypress family (Cupressaceae)- like the Western Red Cedar I mentioned above which is a Thuja (the genus, a step down in commonality from the family), the Eastern Red Cedar of the east and midwest which is a Juniperus, the Atlantic White Cedar actually a Chamaecyparis. Or, the Redwood, which is now considered a member of the Cypress family, too. Of course there is the Yew family (Taxaceae), of which only on the west coast are there trees that grow wild.

I grew up around the Loblolly, Virginia and White Pines (Pinaceae) of the southern Piedmont. I never failed to sneeze my way through May when they would send their pollen out along with the tall hay grasses.

I first met Eastern Hemlock (Pinaceae) and really started to appreciate the soft shade it provided while living in New Hampshire for my first organic vegetable farm job in 2009. When I was off work, I'd wander the dark woods in wonder- watching the small needles move in the subtle wind that drifted through the forests. I later skied with them at Windblown XC, though the snow was thinner under their canopy. I also mourned their death as the forests in North Carolina were denuded of the Carolina Hemlock. The wooley adelgid took its strongest hold when I moved there for herb school in 2012. I have seen the Western Hemlock mostly adelgid free on the west coast intermingling with Redwood and various Fir species. I could write a whole book about my connection to Hemlock.

My grandma, a plant lover, had a thing for Longleaf Pines. 30 years ago, when she owned a hometown family nursery business that she opened in the late 1950's, she was all about starting the trends. In landscaping jobs with my dad, she would plant Longleaf Pines in the front yards of unsuspecting town homes. On one street you can still seem them with their long arms, big cones and extended needles. Crafty folks love these beautiful needles, as they were one of the Pine needles traditionally used for making Pine needle baskets. This tree is rare now because of habitat loss and fire suppression. It greatly depends on fire to reproduce. One of my herbalism mentors, Juliet Blankespoor, had a great love for this plant, and we took time to meet it while on an herb school field trip in north Florida.

Jeffrey, Ponderosa, Sugar, Lodgepole (and Pygmy). These are just a few pines in California that it has been wonderful to get to know, especially traveling with Eric through the lands he is familiar. I've been meeting them and getting to know what elevation they like to live in, whose sap is the sweetest, who towers the tallest.

Foothill/Gray Pine. This Pine I have started to follow around California, watching where it likes to grow. Usually, it is the lone tree towering not very tall above chaparral scrublands. It drops some dangerously heavy and spiky cones, producing fat pine nuts that are very difficult to break open (another fire lover). The soft needles, a lighter blue color, do look ghostly in early morning fogs, as the mist holds onto the needles, making a shimmer. Eric likes to harvest the Pine pollen for medicine from this tree along with Coulter Pine up on Mount Diablo in the Bay area, a place where he spent time as an angsty punk teenager.

Pinyon Pine cones.-Two-needled variety.

Pinyon Pine. I have become increasingly fascinating by the evolution of this plant especially after reading Ronald Lanner's book "The Pinon Pine." I'm going to write a whole post on this plant at some point, but I wanted to mention that the Pine nuts from this tree are easy to crack and are SO much better tasting than the store-bought version. Anyone who has harvested the pine nuts for food, knows its a sticky labor of love and very worth it. It is also an extremely important food culturally for native folks who live in the desert in its range. Last September, when traveling through Nevada, we arrived at night where we were camping, surrounded by Pinyon and Juniper in the Great Basin. We got out of the car, it was dark, and had freshly rained. The smell of Pinyon Pine sap was intoxicating, and the nuts were scattered on the ground as my headlamp spotted them while orienting myself. Later after harvesting, our hands, clothes, camp stove and cast irons were covered in the sap for weeks.

Conifer pitch is extremely antimicrobial. Lately I have been harvesting from Sugar, Ponderosa, Pinyon and Gray Pine. I also consider some of the resins a bitters, and have noticed other herbalists who have spent more time with specific species feel this way, too. If you're lucky you'll find a pile of the pitch on the ground right by the tree, solid as a rock or still gooey and fresh. The plant uses it to heal its wounds so pulling a bunch of it off of the tree is not the best idea. Sometimes a freshly cut tree will have a bunch or even on Pine cones which are sealed shut by the pitch, waiting for a fire to open them and release the nuts.

A friend of mine in California who is quite the plant/geography/ecology expert has been telling me about the evolutionary purposes of Pine saps. The saps don't freeze in the winter because of the terpenes and other constituents it contains. It enables the trees to photosynthesize on days it gets just warm enough. It protects the trees too, from infection. It also protects our human bodies from infection when we use it on our own wounds.

Sagebrush.

Sagebrush, not really a 'Sage' at all in the traditional sense of the category, is a highly abundant and important plant in much of the desert ecologies of the middle and northern parts of the western United States. It is in the Asteraceae plant family, along with Wormwood and Mugwort, not in the Mint (Lamiaceae) family like White Sage, Black Sage, Hummingbird Sage, Spearmint, Beebalm, Rosemary, among others. It makes its way into California's rain shadows taking a spot on dry hillsides or valley floors. It is the characteristic desert plant you may see traversing through the vast desert lands. Many animals depend on this plant for survival. Cattle farming suppresses the ecology this plant creates and thrives on. And, its habitat is often replaced by invasive grasses brought in my cattle. Even with living in a world that requires some form of animal domestication in order to feed the amount of people that want to eat meat, grazing on a rotation giving the sage and other plant friends a break, greatly helping keep this plant thriving.

I have been told that smoking brain tanned buckskin with this plant works great. I have yet to do this myself with Sagebrush. That process usually involves scavenging the right kind of punk wood, just perfectly decomposed enough but not too much and usually produces a lot of smoke that then infuses with the lecithin-rich brains in the hide and permanently preserving the softened state. Plus, it smells amazing. It can be used for natural dying plant based fabric, too. Rebecca Burgess wrote a great book on this that features plants predominately in California or the West but some beyond called "Harvesting Color' that I have loved for a few years now even though there are a few other really good natural dye books out there.

Sagebrush is antiseptic, anti-microbial, slightly anti-viral. All of those herbal actions that really combat the culprits of wounds and infection. I have also learned that it is possibly useful for paper making. And, it was used traditionally for basket weaving. Of course, it was used for smudging space and air, too. Literally and figuratively, purifying the rooms, spaces and places we inhabit. Including our bodies.

Sagebrush has become become somewhat of an artistic muse for me. I want to photograph it, smell it, draw it, and use it in medicine. It's color and personality draw me inwards. It's smell invokes something ancient and quieting. I am drawn to putting it in the wound salve I make out west for so many reasons that are hard to put into words.

Triumphantly trident. The leaves have three segments like a trident does. The species is 'tridentata.'

Creosote bush.

My first experience was this plant was when I gave an seemingly unruly and black jean clad herbalist named Sevensong a ride across New Mexico from the formerly Traditions in Western Herbalism Conference to the Anima Sanctuary in the Gila National Forest in 2012. I drove out to the conference from Kentucky, where I was living pretty much in the Daniel Boone National Forest at the time, with friends who somehow found me there under the sandstone cliffs to carpool together. Mario, who was Sevensong's apprentice at the time, and Nina, who I had just lived and worked with at the Goldenseal Sanctuary in Ohio the following Spring, took off together for a 24 hour straight ride to arrive at the conference at dawn when first classes began. Fast forward to after the conference and Sevensong and Mario were invited to come out and visit Kiva, Wolf and then Loba- so Nina and I came along because we were the ride. Mario was adamant about getting Chaparral. Given that Sevensong focuses so much on first aid, he was a good passenger to have on the trip. Of course, his witty humor was always a treat, too. Chaparral is a commonly used and important plant for wounds and infections of the like. I had never seen it so I didn't know what we were looking for at the time. As a matter of fact, I had never even been west of the Mississippi at the time, and the only deserts I had experiences were in northern Spain when I walked the Camino de Santiago, parts of Italy and Greece when I traveled there as a teenager, and in parts of Peru where not a single plant grows. I had never seen the deserts of the U.S. Sevensong kept his eyes peeled for vast fields of the scrubby plant and after hours of windmills and immensity, he spotted it. Over a barbed-wire fence and up a big hill. We pulled over and got our bags out, and made our way towards the fence, ominous storm clouds drifting around right on the other side of the bare hill. We awkwardly hopped over or climbed under, getting covered in dry desert dirt. Walking up to the plant, I could hardly believe this thing was even alive.

One crack of a gnarly limb and holding it up to my nose sent a profound waft in the air- the smell of pure solitude, of harsh sunshine, of dry survival. Quietly for nearly 45 minutes we collected the twigs for later oils and tinctures.

I didn't see it again for years. Eventually, I made it back to the desert, and this time in southern California. When I saw it again from a distance, I immediately knew. I just don't seem to forget some plants after even meeting them once. Their color and aura call out to me and in the case of chaparral, sometimes from a mile away. It is astounding how much this plant can withstand such a harsh climate as the deserts where it lives. Hence why its medicine is so powerful: the shrub sends down deep roots to find the tiniest bits of water to hold onto. It produces the aromatic and intoxicating resins in its body to protect it from the harsh conditions. The plant is know for dealing with infections, rashes, cysts and the like.

plantain.

Plantain is one of the first plants most people learn. I too spent a lot of time with this plant when first studying herbalism. Even though I grew up with it everywhere, filling the cracks of the pavers in my grandma's tropical greenhouse, or the gravel of my parents' driveway until my dad sprayed roundup to kill them, I never really truly noticed them until I worked at Stonewall Farm in New Hampshire in 2009. I grew up around plants and plant lovers but for some reason, the cycles of plants and seasons had never really clicked in my mind until I left and worked on a farm that grew food. My first tasks were the long hours on our hands and knees pulling up weeds to prep the beds for transplanting because we did not machine-till. Alongside yellow dock, burdock, mint, dandelion, and chickweed growing in the garden beds was plantain. It was harder to pull up than the others. We had to dislodge it with hand trowels. I remember spending hours on one bed that was more compact than others, full of nothing but plantain. At the time I was also doing my first herbal apprenticeship nearby on the weekends in Brattleboro, VT. Rebecca was introducing me to the most basic and abundant 'weedy' plants first, and I would go back on the farm where I pulled these same weeds everyday and ususally composted them. I started to make medicine from them.

I remember going to the Maine Common Ground Fair one year and taking herbal medicine classes in the herb tent and Gail Faith Edwards taught a class on plantain. She even had it in a pot growing to show us. It is also known as "white man's footprint' because it followed the white folx from Europe to the Americas in their colonializing and never left. I didn't know such a common and abundant plant has such great medicine. It is great for wounds, internally as a mucilage, and edible when young. The seeds are psyllium, a good fiberous clean-you-outer. I use this in salves and cremes whenever I can get my hands on it, which is usually anywhere I live or travel! If you're in a city walking around, you're likely to see it in the sidewalk, or next to buildings. If you till your lawn for a garden, you're likely to see it pop up if it wasn't already there. As kids, we would find a way to tie up the seed heads and shoot each other with them.