Resting gently in my heart and mind are the days I spent at the Croft homestead this past month engaging with the incremental parts and pieces of things that have to come together somehow. I have been watching the land’s birthing process in new ways and how the things we use and cherish come from it. At this place, a kind of magical world stuck in another time, the birthing of things are easy to witness, be a conduit for and gain blisters from.

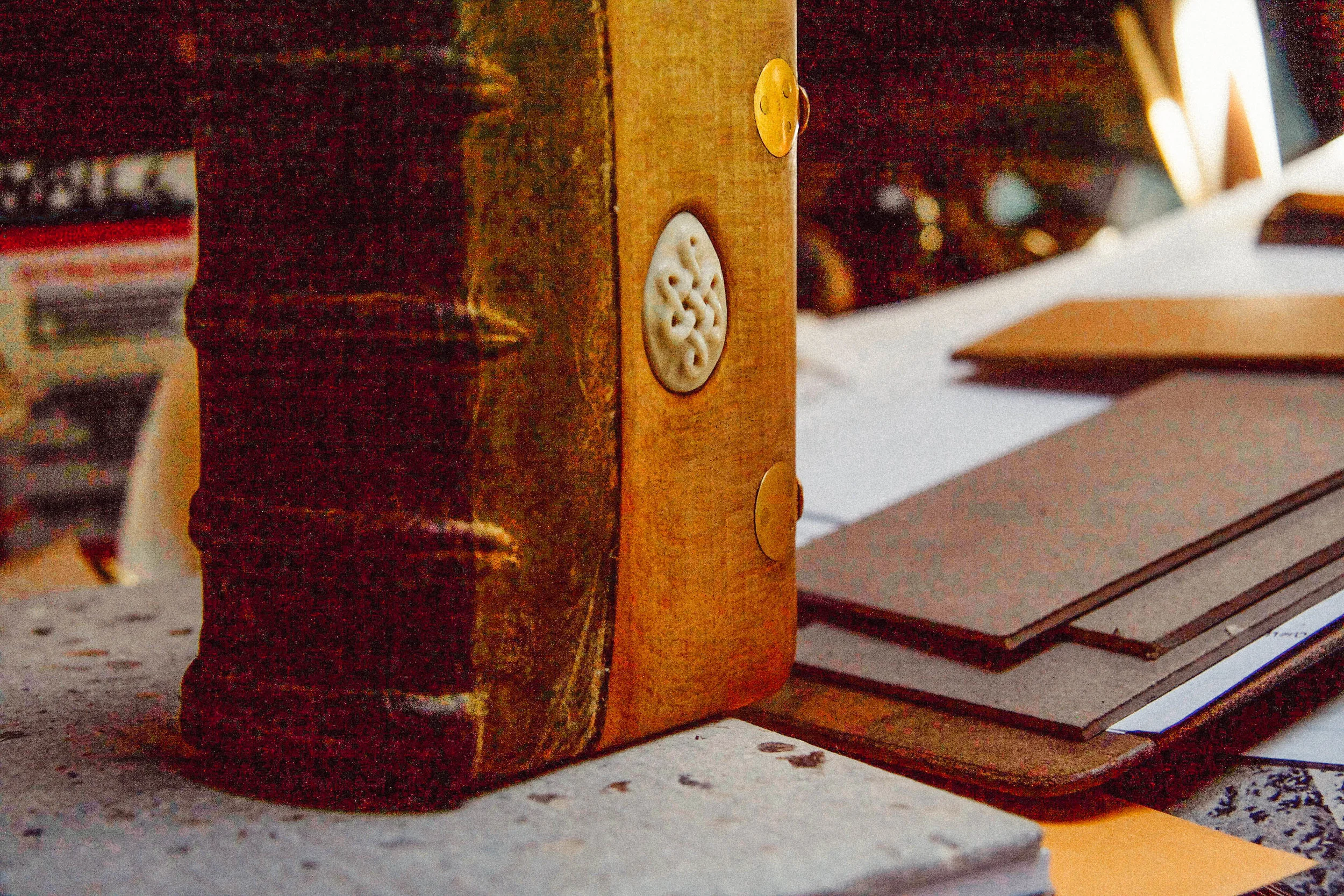

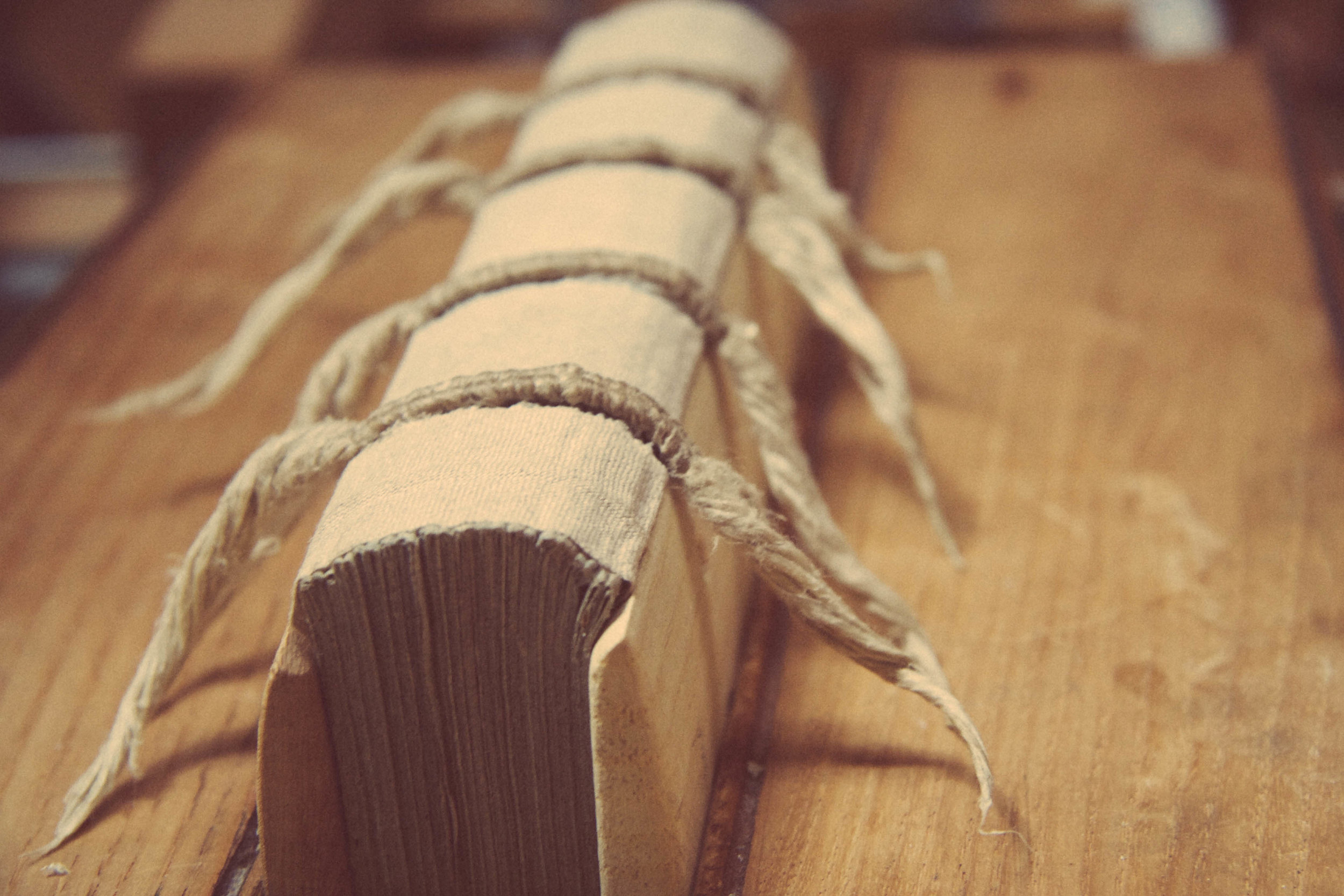

One of Jim Croft's amazing handmade books.

One of Jim Croft's handmade books.

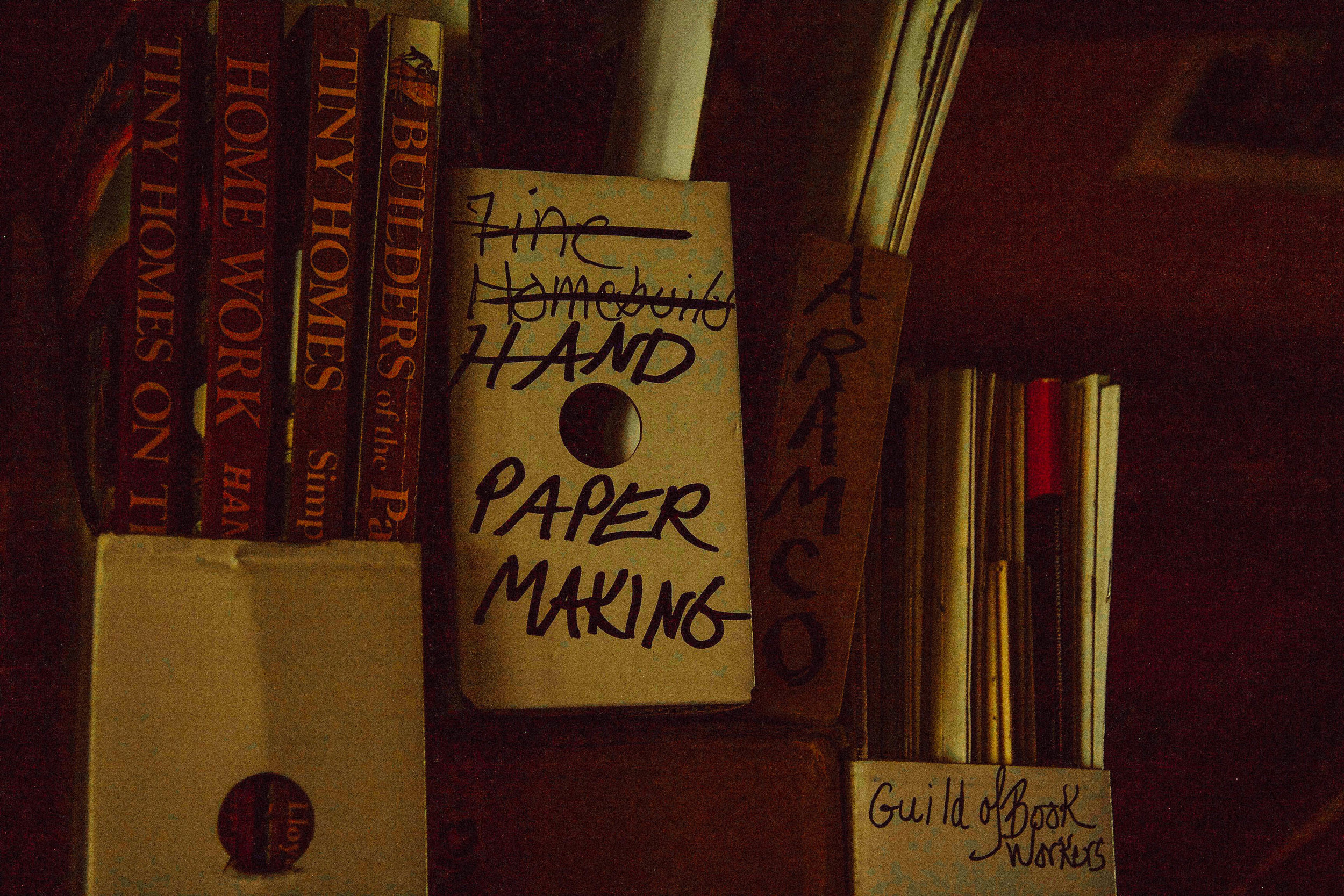

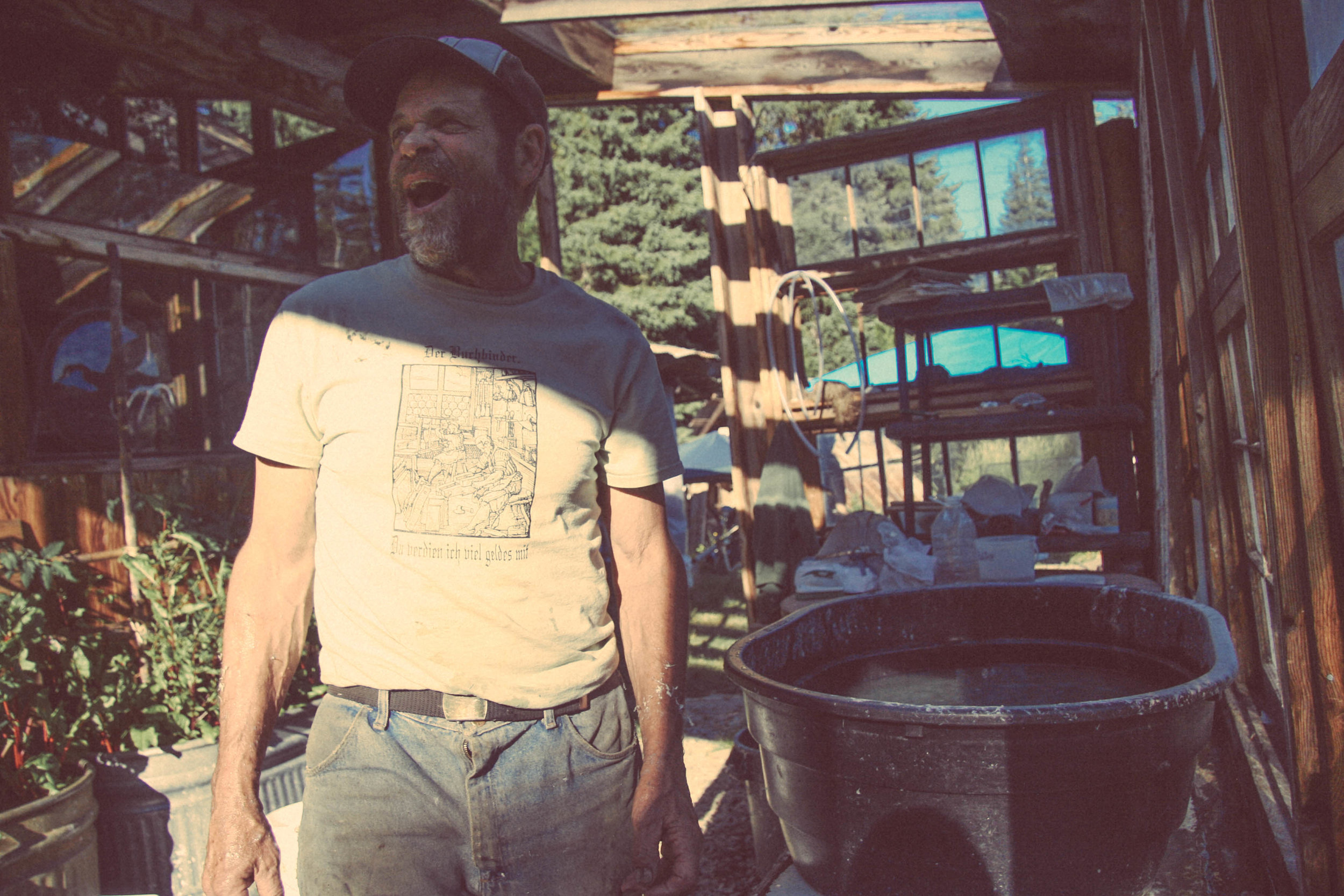

The Crofts include Jim and Melody, amazing craftspeople who settled in northern Idaho in the early 70’s. They have watched various other back to the lander neighbors come and go, but they have remained. Every summer they host visitors and also hold classes on making medieval books from the ground up.

They have an off grid house that merges somehow gracefully with workspace, so from wake up to sleep they are pursuing their craft. It is equipped with solar power they installed in the early 80’s. They also have other cabins and structures on the land: including a well designed and highly functional outdoor kitchen with water catchment, wood cookstoves. A cabin for guests with 5 beds. A treehouse bungalow tucked up in fir trees.

Main house and wood shed.

Guest cabin.

Inside the guest cabin.

Inside the guest cabin.

Treehouse / Guest house.

Inside the treehouse.

In the main house.

During my time there, which included hide tanning experiments with Jim before and after the bookmaking class started, I learned a lot about working with materials I don’t have as much experience with as I would like: brass, iron, bone, wood, flax and hemp fiber. The materials and what it takes to work with them requires time spent being a part of their transformation. Each of the elements has tools and loose rules associated with them, as well as processes that we can easily mechanize. But here we slow down and revisit the role humans have had historically with those processes even if we are uncomfortable with the slowness of it via the making of a handmade medieval era book. As time really is relative.

These processes have become sacred. They always were, but because as a society we have drifted faster and further into hyper speed it is even more so. The things we use everyday are made in mass mechanical amounts to the lowest common denominator quality pumped out without spirit and thrown at us to consume and dispose, over and over. Maybe it is to keep the machines happy or those that control the machines to fulfill the greater and greater need to replace spirit with empty plastic amulets of materialism.

Ocean Spray.

St. John's Wort.

Serviceberry.

Nasturtium.

OXE-EYED DAISY.

WESTERN HEMLOCK.

When we make things [even if it is simply pie], we are channeling the elemental spirit of what we use. The wood that comes from a tree whose life has seen much change, growing in spirals seen when slowing and looking close to sand the layers smooth, splitting in the round and watching the medullary rays emerge. The language of the tree's life is hard to ignore. The language speaks in splinters and beautiful tanned colors.

The fire that smokes the dry rotten punk wood into a bag sewn of a softened deer's skin, made with the shavings of hand planed tree of heaven, beech, cedar or sycamore boards split well for book covers.

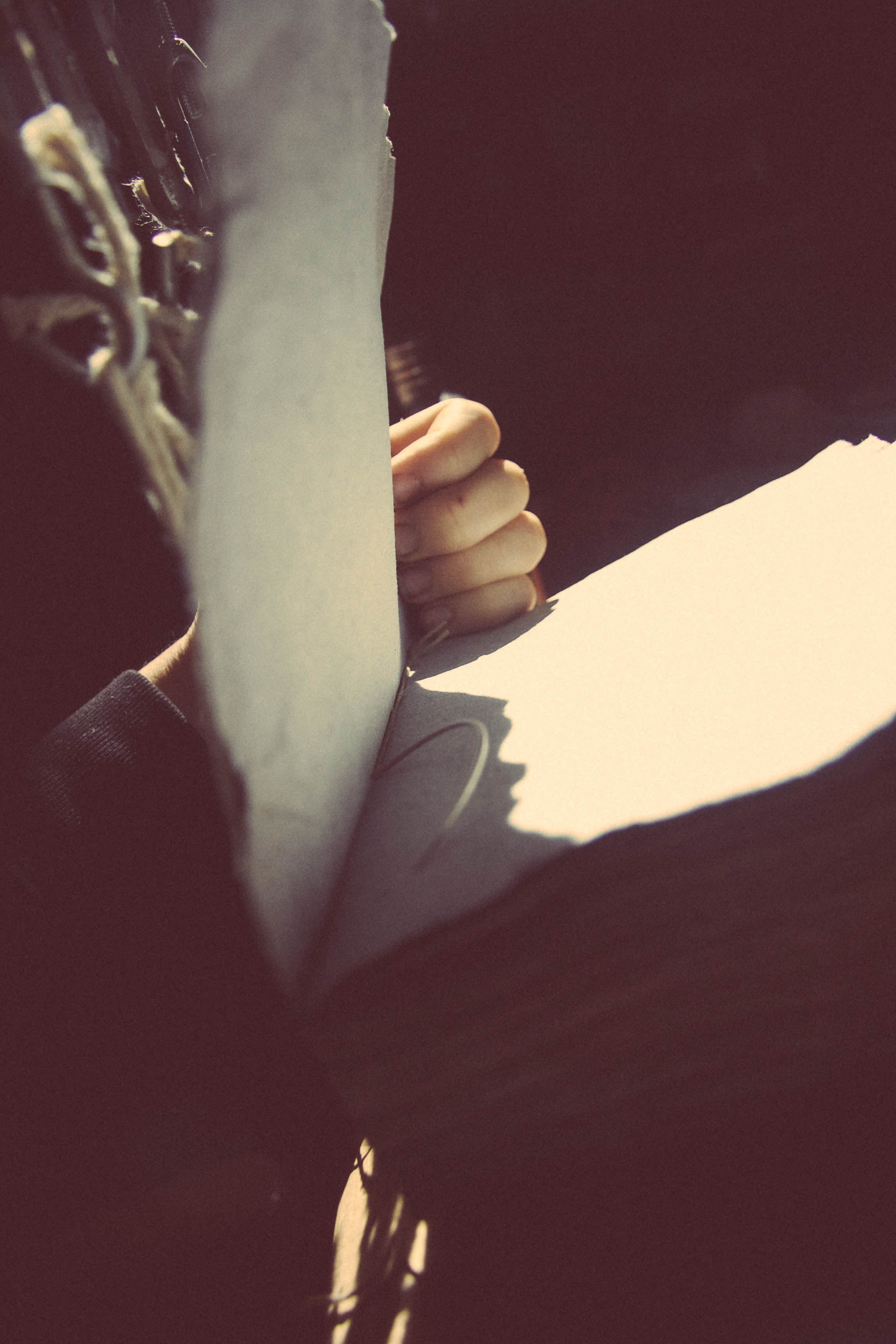

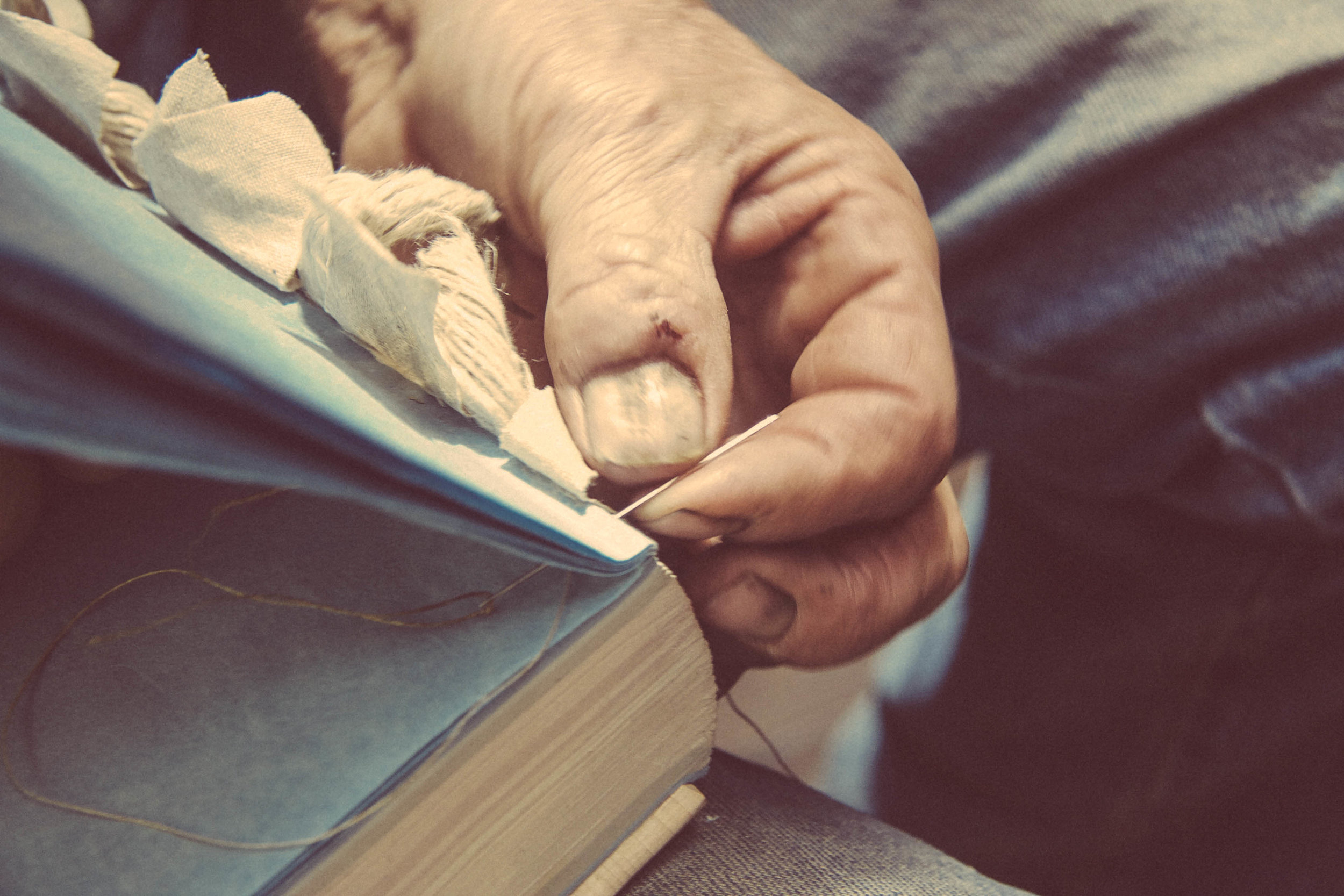

The flax thread that hold the book, or the leather straps, or the child's vest together. Soaked in water that the tree drinks, that we drink, that we use to make the paper for the book.

That puts the fire out at the end of a hide smoking, the skin permanently changed, the animal's life reembodied, by the work of our tired hands, witnessing.

The metal we hammer out, to hold our books together, to reheat the axe heads after a house fire that has changed their molecular structure, to be part of the rebirth. Of reuse, of handling the elements carefully.

Machines can only go but so far before they become our gods.

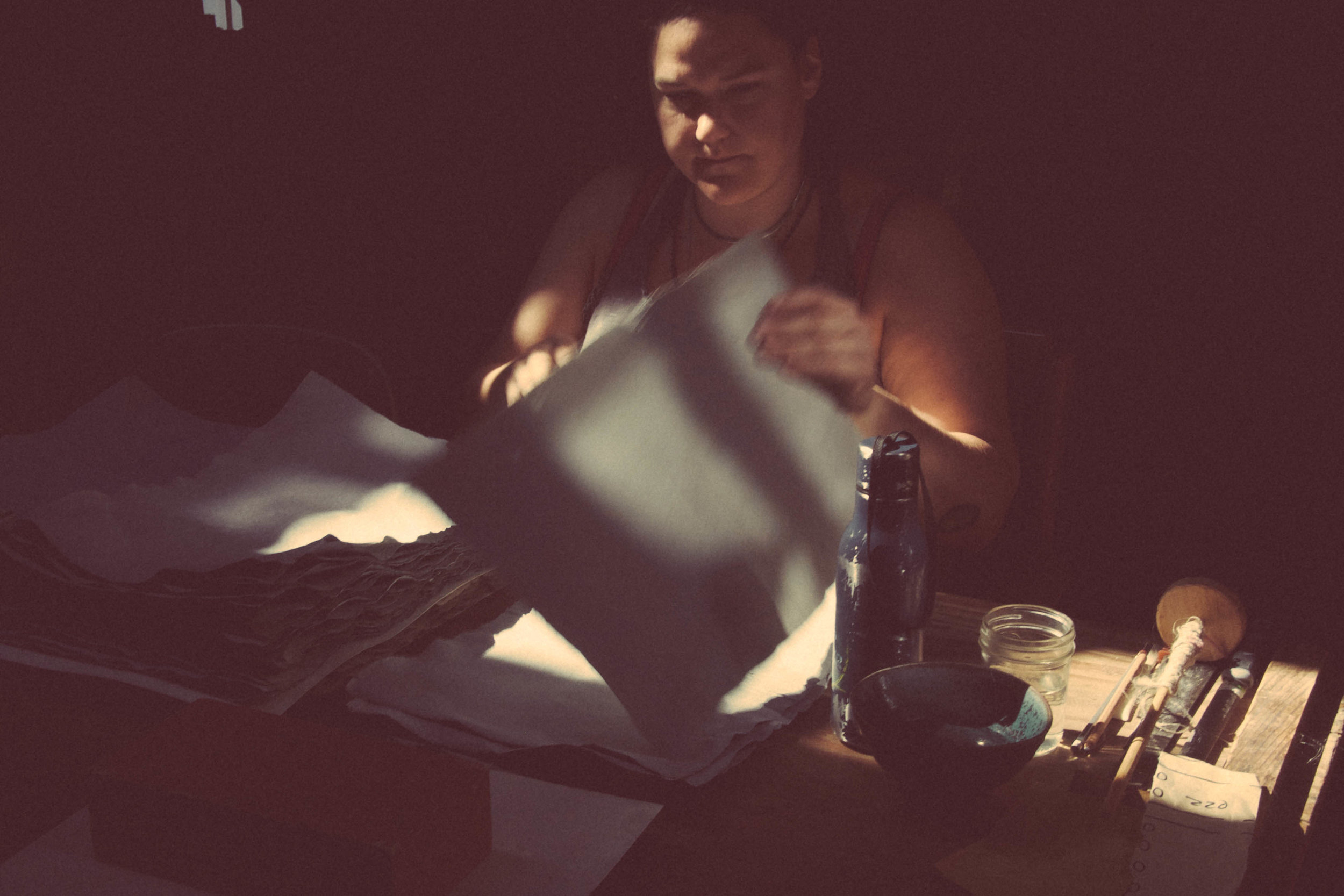

Where is the fine line, I wonder, as I smooth the bone folder tool across wrinkled air-dried paper handmade from old blue jeans and homegrown hemp; between tools that gently aid and tools that replace the spirit that connects living things together.

I chat nightly with Ian, the brilliant blacksmith from South Carolina/Virginia who is helping Jim rebuild a paper stamp mill. We talk about the nature of technology in our worlds.

I am reminded of the concept 'techne', of the class I took in college on the philosophy of technology over ten years ago, on our talks about where it went all wrong, or how we saw tool and architectural use and design become overly masculine.

When does a tool help or inhibit us? Is the tool designed with the feminine in mind? Harnessing the gentle integration rather than the marched upon?

The fire is merely embers, smoking at the barely structured dry punk wood [old douglas fir] merging with the egg yolks wrung and beat into flesh and fiber to lubricate and make soft tenacious glues that hold us all living things together.

The fire heats the axe head, glowing orange, dipped quickly in cold water and moved along its side in the water, to orient the particles. Looking closely at the colors of straw and sky in the iron, like the field of wheat waving in unison under hot summer sun across western Idaho; oh to to see the element transform.

The water holds our hides, infused with hemlock bark stripped from a dead tree, heated over a wood cookstove. The tannin traps and tightens and slowly pickles the death away, for a little longer all least.

The water suspends our hemp and cotton pulp, that is pressed onto wool blankets, and pressed with wood and metal to drain the excess water, solidifying crisscrossing fibers. So we can write poems about the process our minds and hearts go through daily being humans in a world that wants us to compete with complicated machines.

It could go faster, the tanning, the fiber beating, the book binding, the basket weaving. What good does it do to speed up time, to compete with machines, in the end? Can we get any faster and not become sick? Are we already sick and convinced it is normal?

Being at the Crofts, these questions, reflections, images come and go as I spend my days filing bones, carving wood, folding paper, hammering brass, skudding the extra liquid out of the skins of animals hunted for their bodies' sustenance.

Jim's main focus is bookbinding, specifically medieval era bookbinding. Turning 70 years old in October, he has made it his life's work to construct books with the simplest tools possible and working directly with the raw materials that make up those books. His activism is simply the pursuit of the process and slowing down. Yet, he is up before dawn and still doing at dusk. His art is how he lives his life: recycling and repurposing everything he finds rather than buying things new whenever possible. He engages the land daily in conjunction with the passions in his life on a raw and direct level. Caring for hand tools, collecting fibers for paper to go in his books, cooking down bones removing ligaments and fat to make bone tools, finding treasure in thrift stores like ancient abused pocketknives and bringing them back to life.

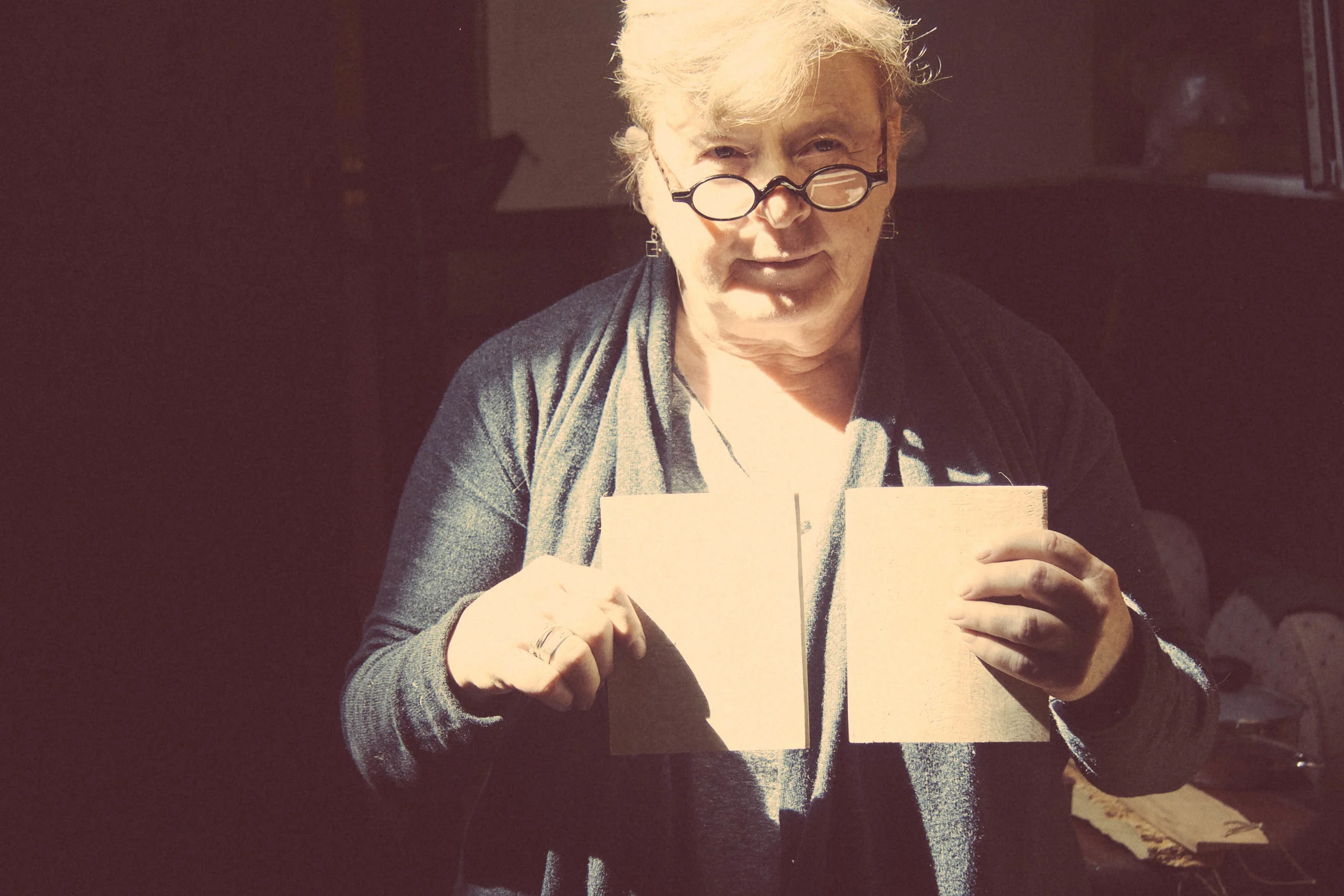

Melody weaves intricate baskets from the roots of her tree friends. She gently digs when she feels called and splits the roots, dries and soaks them, and spends months on one basket, inventing her own designs or using universal cultural symbols that all humans can relate. She gently spins flax on her spinning wheel, makes her plantain salves, crochets lace on the cuffs of her handmade wool children's sweaters she sells at barter fairs and farmer's markets.

Jim and Melody, together are married to the land. They spend more time with the trees, the fire that cooks their food, in the shade of the plum trees that protect their gardens than they do with humans. Yet, they love sharing their crafts and the love of the land and the process.

I feel gratitude for a glimpse into their life and hope to spend more time there learning from their wisdom in the future.

'Never give up,' Jim says.

The key to figuring out how to make his books, masterpieces that are only possible with time and dedication, is to keep going despite failure.

Why abandon the land because it is hard? Why abandon our dreams because we are told they are crazy? Where do we really get the framework for right and wrong these days, in a world that tells us that buying plastic and sitting in florescent lit rooms is more natural of a God than a day spent picking serviceberries under a July sun?

Maybe that higher power, whatever it is you want to name it, within us, below us and above us, all around us calls us inevitably to at least consider the connection to a tree, it's growth rings and spiraled life resembling something much like how our infancy is like our last breaths.

How can I ever do anything else but be a part of that connection if it has become my spirituality?

To make, to channel, to use my hands to transform death to life again, or make life death with careful consideration. To inspire others to do so.

Being at the Crofts, making books, paper, bone buttons, sharpening my knives and gouges, refining wooden tools and boards, spinning flax into fine thread, scraping flesh from deer skins, reminds me of what is most important.